Play Promotes Learning

Adults often give the greatest importance to the things that they can most easily see. Reading, writing, and math certainly fit into this category. It is easy to see a child’s markings on a paper. These markings show us that the child’s brain is processing thought. But there are other key aspects and indicators of brain processing that are not as easily seen on paper. Erika Christakis asserts, “…with limited time in a day, every minute spent doing rudimentary skills such as alphabet drills or simple addition work sheets is a moment not spent on complex skills such as working collaboratively with peers to build a pulley system or a fort. Simple and complex skills are not mutually exclusive, of course, but, as we’ve seen, the former is a by-product of the latter. It doesn’t work the other way around” (“The importance of being little”).

Simply said, children’s play in a material rich environment is stimulating to brain processing and function, allowing for complex skills to form, which in turn promotes the simple skills. Play enriches the brain’s ability to think collaboratively, critically, and with an open growth mindset. It introduces opportunities for communication, conflict resolution, confidence, and respect for others. And, in addition to all of this, play does, in fact, open the joy of literature and math to children in simple, natural, and exciting ways!

Literature in Play

Literature includes critical thinking skills, deeply considering characters, themes, and messages. A foundation in literacy includes letter recognition and vocabulary.

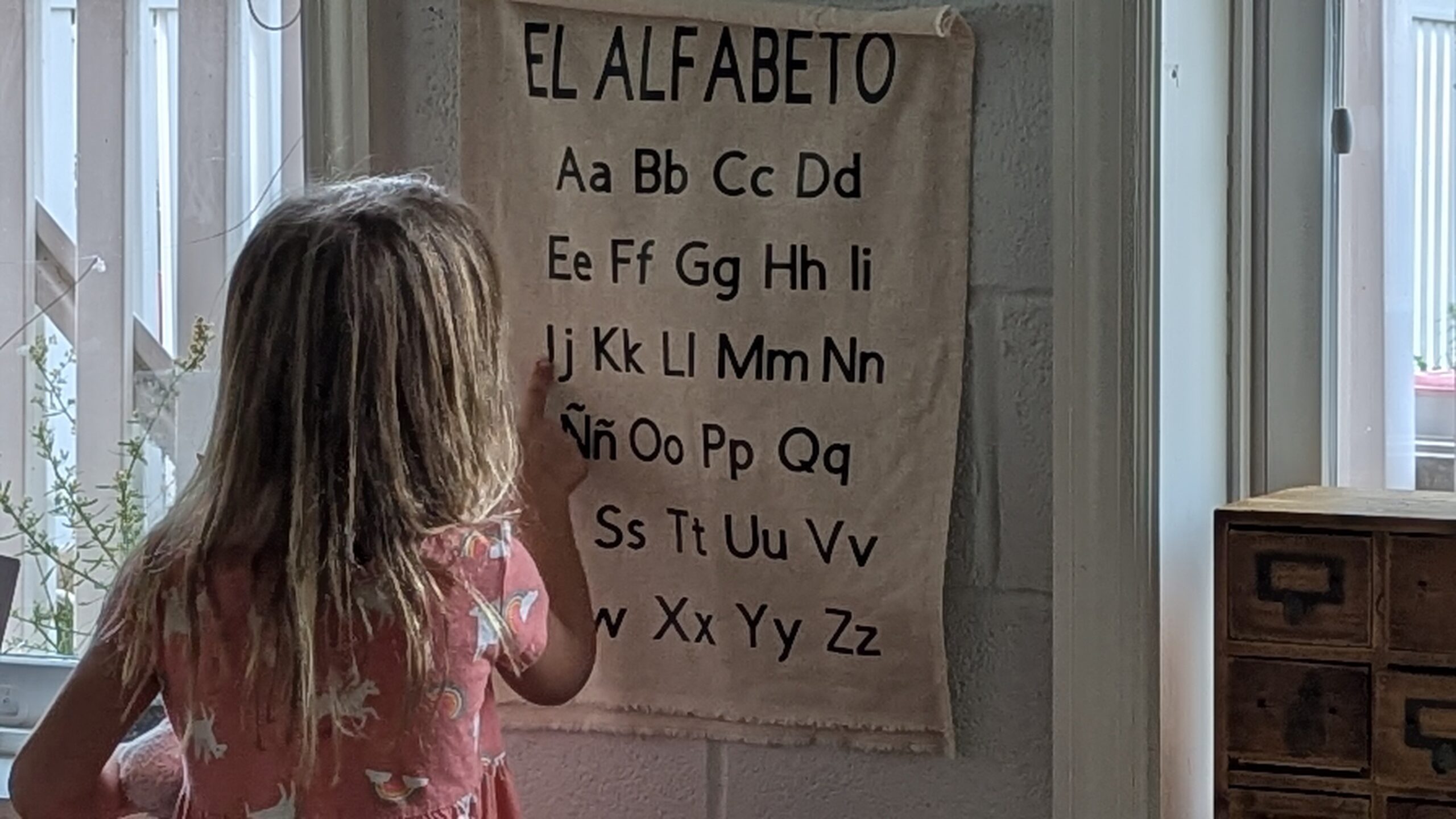

Tools, such as a marker, are useful for children to transfer ideas from out their mind so others can see them. The act of using tools requires fine motor skills and is foundational to learning. Another tool can simply be a finger. Using a finger to trace the letters, or other objects helps build recognition in the brain.

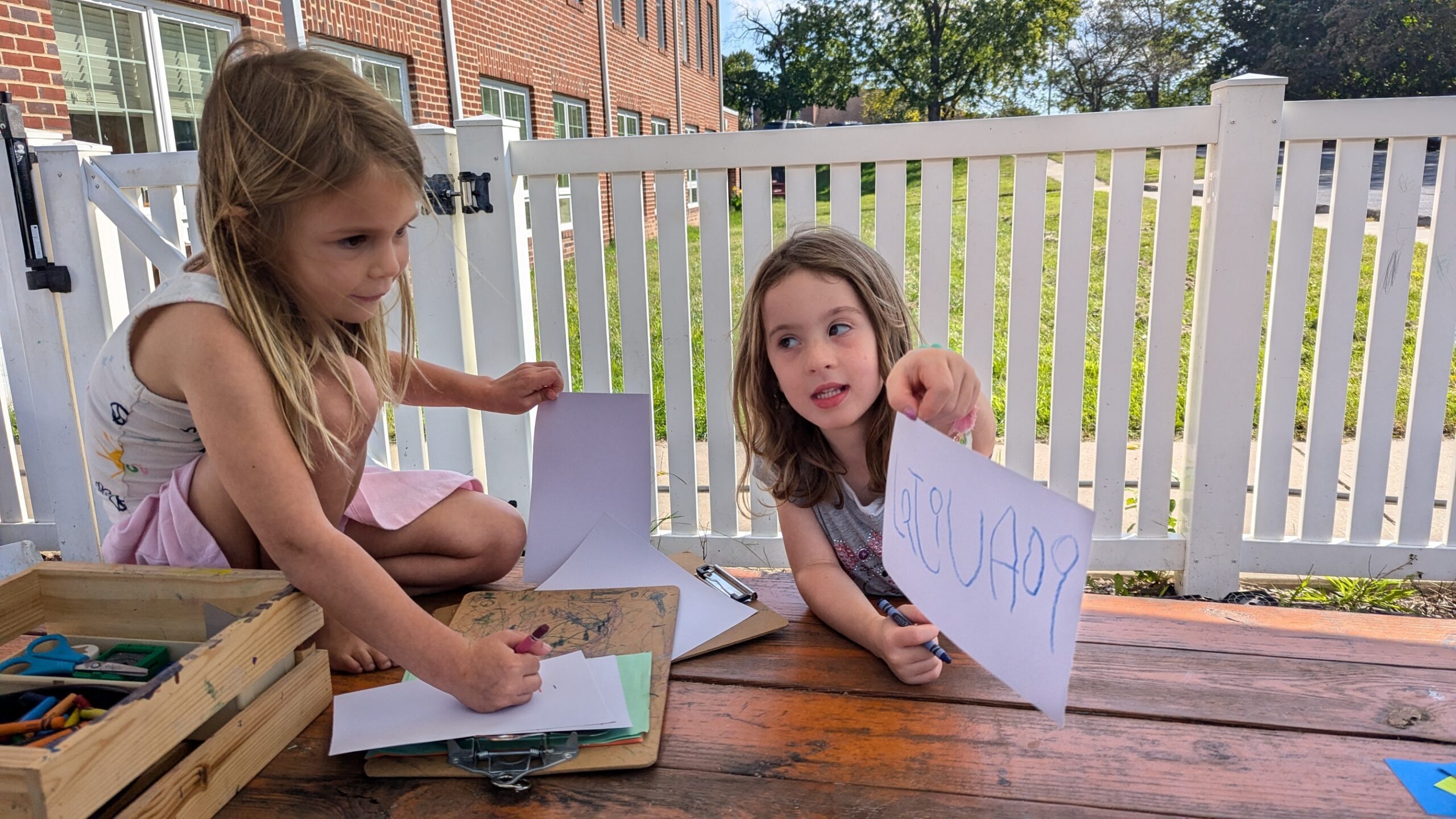

Two children put some letters together and then asked the teacher what word they wrote. They knew that different letter sounds can come together and make a word. They are given time to explore this interest.

This collaborative work of art (chalk around the planter wood) required skills used in literature, including considering the messages that each child wanted to convey, and following a theme.

Letters can become a part of play in many ways. This child uses letters to make a string necklace. Often, as children play with letters, they will ask what the letter is, or if their creation makes a word. At these moments of interest, teachers have the greatest opportunity to make a big impact on the child’s literacy learning, because the child’s mind is open and ears ready to hear.

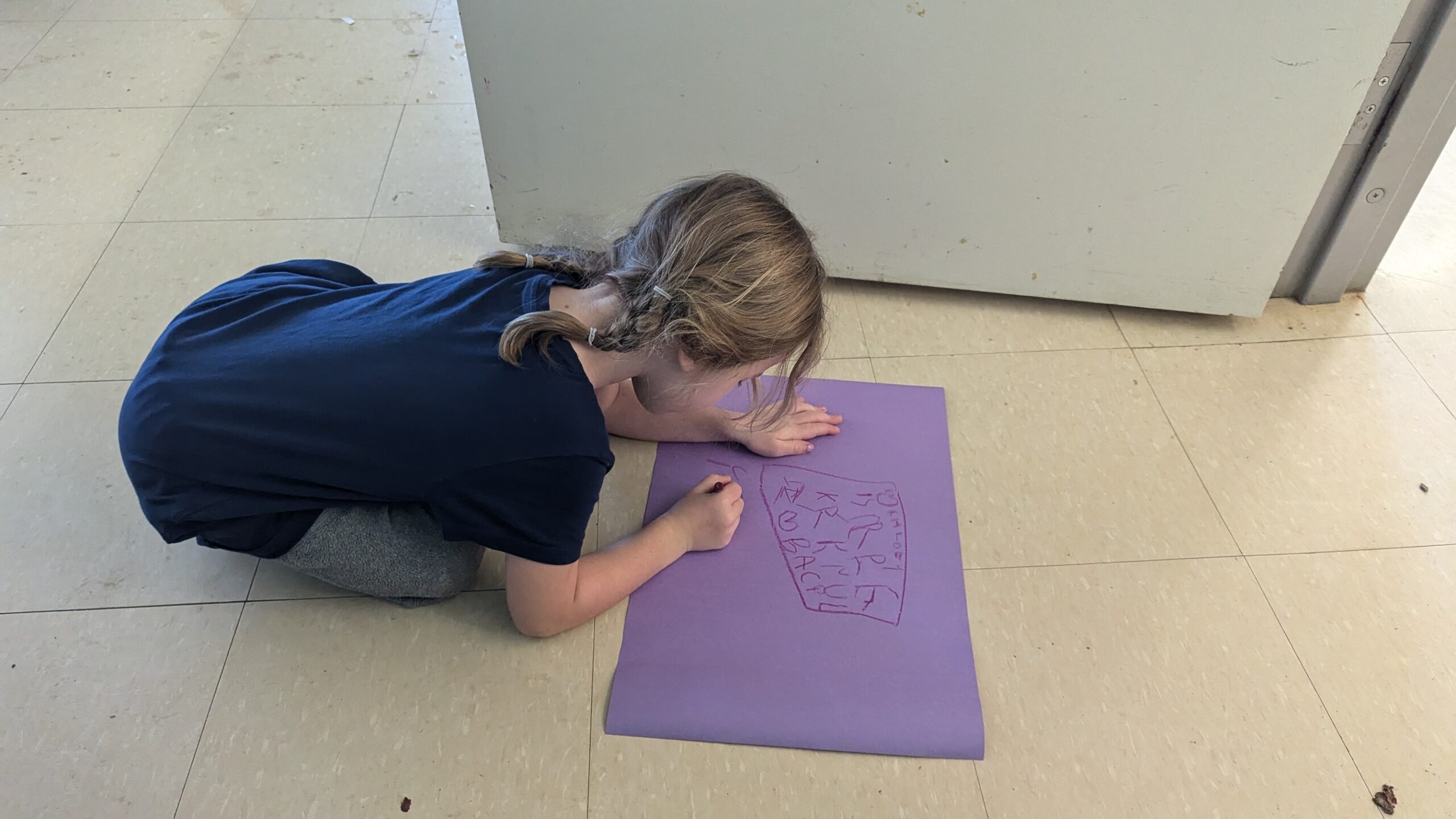

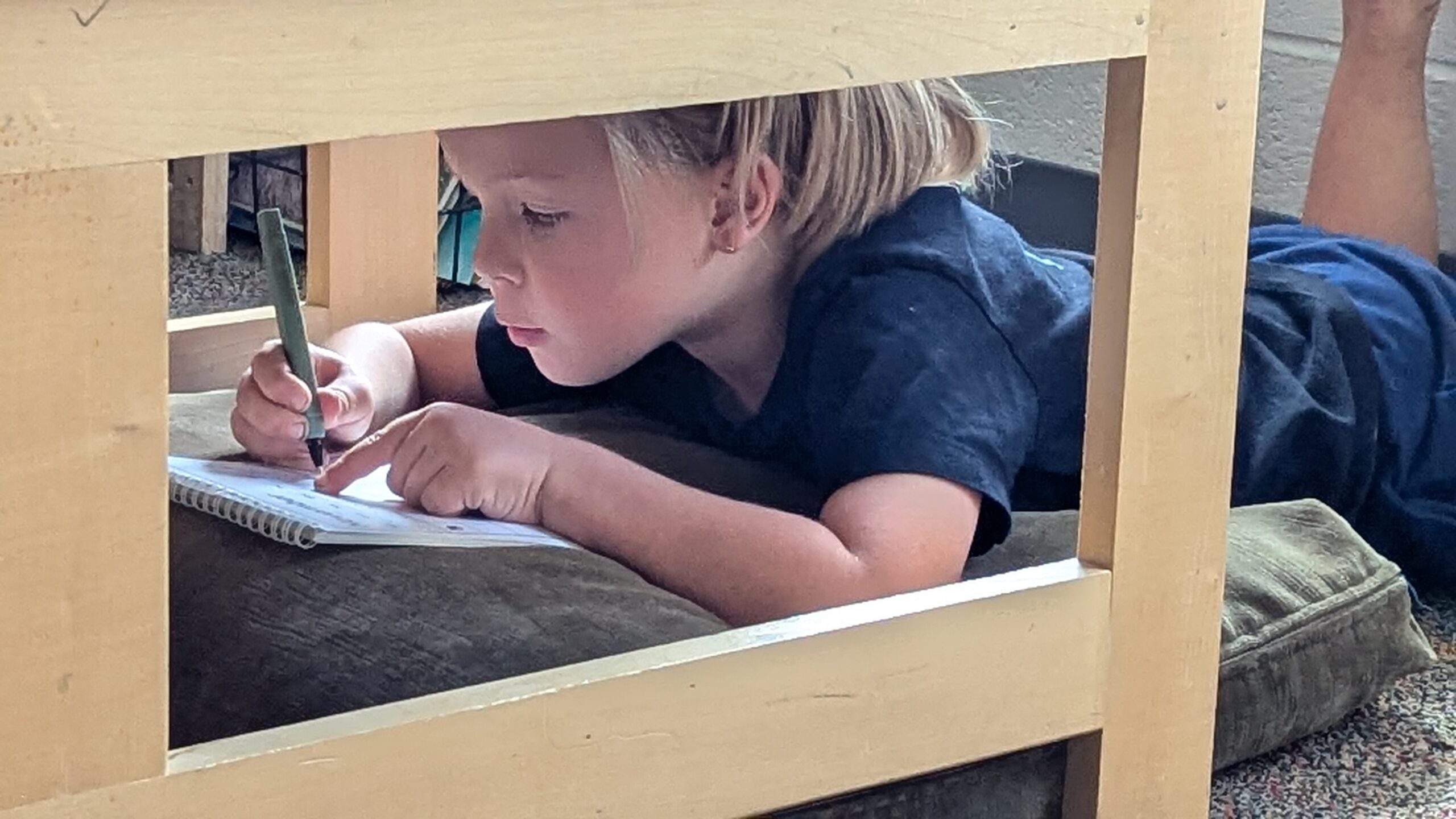

Sometimes, in order to write or be creative, a child needs to find a comfortable place. An inspiring place. And trust that they are okay in doing so.

Sometimes literacy comes as a by-product of play. Words and pictures of pizza are noticed on a wooden toy house, as a group of children create a village. A child seeking a moment to relax with a blanket notices a poster on the wall that classifies different animals. He studies it for a while.

Math in Play

Foundations in math include sorting, counting, building, measuring, noticing patterns, making comparisons, recognizing numbers and shapes, describing an environment, and problem solving. These skills are exercised consistently in play.

Numbers and alphabet letters are sorted and explored

A measuring tape includes number recognition, and helps the children with measurement and comparison. When one child learned what a measuring tape was, she asked to measure her size when she was laying down.

Sorting beads not only supports math concepts, but also helps with fine motor skills, which will increase ability to hold a pencil and write.

The children made up a unique game together using dog-themed Uno cards. As each card is pulled, they determine together where it belongs. They sort the cards into like piles. Math shows up in dramatic play, science, building, manipulatives, and so much more!

Reading and Play

The ability to read comes through phonics, vocabulary, fluency, and more; all of which surround constant introduction to words over and over again. Stories are engaging for many reasons, and children often seek out stories and words in their play.

An adult is not always needed. The more a child hears a book, the more they are able to pick out key words, or match thoughts with just the pictures. “Reading” to your peer is confidence building and socially strengthening.

When we read a book to the children it’s not just about getting from page one to the end. The story can spark so much conversation, questions, statements, etc. there might be a story about a dog, one child yells out “I have a dog!” more children chime in, questions are being asked, “Do you have a dog? What color is it? Is it big or small?” We might come across a word that’s not common and ask if anyone knows what that word means. Sometimes when we read a less common word one of the children might ask, “What does that mean?” Books are a wonderful way to connect with each other!

A parent volunteer takes time to read with the children. One book often becomes many, as the children bring over more and more, according to their interest. Reading indoors is fun for finding a special spot to read individually, or with friends. But Reading isn’t quarantined to just the inside! Reading outside can be exciting too. It is as if, being in our natural environment, with the natural sun light highlighting each page, reading becomes even more a part of who we are. |

Play will always be a good way to build foundational literacy skills because, as Fred Rogers said,

“Play gives children a chance to practice what they are learning.”